Intimate image abuse – despite increased reports to the police, charging rates remain low

by Bo Bottomley, Senior Policy Officer and Dr Michaela Bruckmayer, Research Lead

Intimate image abuse, often referred to as ‘revenge porn’ is an increasingly common form of domestic abuse. Perpetrators share or threaten to share intimate or sexual photographs or films of a survivor, without their consent, as a tool of coercive control and to inflict emotional distress on them. The act of sharing or threatening to share intimate images on the internet, or with a survivor’s family, friends, employers, or new partner has a devastating impact on women’s mental health and physical safety and often leads to social isolation and economic harm.

Refuge’s specialist Technology-Facilitated Abuse and Economic Empowerment Team was launched in 2018 to support the growing number of women experiencing abuse perpetrated through technology, including intimate image abuse. Despite it being a criminal offence since 2015 to disclose private or sexual images without consent and with the intent to cause distress to the victim, many of the women supported by our specialist tech abuse service express that they receive a poor response when reporting these crimes to the police. Examples of this include victim-blaming and cultural insensitivity, lack of understanding around the nature and impact of technology-facilitated domestic abuse, and a failure to gather evidence. Alarmingly, women whose perpetrator threatened to share intimate images were not protected by under this criminal offence. Some of the women Refuge supported were told by officers that there was little they could do if an image had not been shared, and to come back when their perpetrator had actually done so.

Research conducted by Refuge found that 1 in 14 adults (equivalent to 4.4 million people in England and Wales) have experienced threats to share their intimate images without their consent. Often, the perpetrator is a current or former partner. During the passage of the Domestic Abuse Bill, Refuge campaigned tirelessly to extend the revenge porn offence to include threats to share private and sexual photographs and films without the pictured person’s consent. Following our campaign the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, extended Section 33 of the “2015 Criminal Justice and Courts Act” to criminalise threats to share intimate images. to criminalise threats to share intimate images.

The new legislation came into effect in July 2021. However, since then, Refuge has not supported a single survivor whose perpetrator has been convicted following a report of threatening to share an intimate image to the police. This compounds the overall picture of poor police response to intimate image abuse. Furthermore, Refuge has received little information from government about how it plans to monitor the implementation of this new offence.

To get a better understanding of the situation facing survivors when reporting intimate image abuse to the police, in July 2022 – one year after the offence was expanded – Refuge followed up directly with police forces to inquire about the number of recorded intimate image offences as well as the outcomes for this offence from January 2019 to July 2022. We sent freedom of information (FOI) requests to 43 police forces in England and Wales, and received responses from 29 forces, 24 of which were complete and could therefore be included in our analysis. Refuge asked for information specifically on the number of intimate image offences recorded by police forces as well as four different crime outcomes, including charged offences, and cases that were dropped by the police due to lack of victim support or difficulties in obtaining evidence:

- Outcome 1: Charge / Summons: A person has been charged or summonsed for the crime

- Outcome 14: Evidential difficulties victim based – named suspect not identified: The crime is confirmed but the victim declines or is unable to support further police action to identify the offender.

- Outcome 15: Evidential difficulties named suspect identified – the crime is confirmed, and the victim supports police action, but evidential difficulties prevent further action: This includes cases where the suspect has been identified, the victim supports action, the suspect has been circulated as wanted but cannot be traced and the crime is finalised pending further action

- Outcome 16: Evidential difficulties victim based – named suspect identified: The victim does not support (or has withdrawn support from) police action.

Table 1: Police forces’ responses to FOI request

| Police force | Data provided? | Included in analysis? |

|---|---|---|

| Avon and Somerset Constabulary | No | No |

| Bedfordshire Police | Yes | Yes |

| Cambridgeshire Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Cheshire Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| City of London Police | Yes | Yes |

| Cleveland Police | No | No |

| Cumbria Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Derbyshire Constabulary | Limited data provided | No |

| Devon and Cornwall Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Dorset Police | Yes | Yes |

| Durham Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Dyfed-Powys Police | No | No |

| Essex Police | Limited data provided | No |

| Gloucestershire Constabulary | No | No |

| Greater Manchester Police | Yes | Yes |

| Gwent Police | Yes | Yes |

| Hampshire Constabulary | No | No |

| Hertfordshire Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Humberside Police | No | No |

| Kent Police | No | No |

| Lancashire Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Leicestershire Constabulary | Yes | Yes |

| Lincolnshire Police | No | No |

| Merseyside Police | Yes | Yes |

| Metropolitan Police Service | Limited data provided | Yes |

| Norfolk Constabulary | Limited data provided | No |

| North Wales Police | Yes | Yes |

| North Yorkshire Police | Yes | Yes |

| Northamptonshire Police | Yes | Yes |

| Northumbria Police | No | No |

| Nottinghamshire Police | No | No |

| South Wales Police | No | No |

| South Yorkshire Police | Yes | Yes |

| Staffordshire Police | No | No |

| Suffolk Constabulary | Limited data provided | No |

| Surrey Police | Yes | Yes |

| Sussex Police | Yes | Yes |

| Thames Valley Police | No | No |

| Warwickshire Police | Yes | Yes |

| West Mercia Police | No | No |

| West Midlands Police | Yes | Yes |

| West Yorkshire Police | Limited data provided | No |

| Wiltshire Police | Yes | Yes |

For this analysis, only complete responses to the FOI were included. The exception was data provided by the Metropolitan Police, which was still included despite not providing a full response. This police force provided the total number of recorded offences charged from Jan. 2019 to July 2022. However, in the breakdown shared by year, they had redacted the number of offences charged for the years 2021 and 2022 (until July). The Metropolitan Police let Refuge know that this was because the number was so small that there was a risk of identification of victims.

This blog only focuses on totals from Jan. 2019 to July 2022 and does not break the data down by year, which allows for the data from the Metropolitan Police to be included. Data from other police forces that only partially responded to the FOI was deemed too limited and was therefore excluded from the analysis.

What we found

Despite a steady year-to-year increase in recorded offences, only about 4% of offences were charged

From January 2019 to July 2022, the 24 police forces who responded to the FOI request recorded a total of 13,860 intimate image abuse offences. Police forces’ statistics do not distinguish whether an offence constitutes the disclosure or threat to disclose an intimate image, or both.

There has been a steady increase in the number of offences recorded from year to year. There were 26% more offences recorded in 2020 than in 2019, and a 40% increase between 2020 and 2021. In the first six months of 2022, more offences have been recorded than in all of 2020.

This is a positive sign, as it could suggest that both more intimate image abuse is now captured by the criminal law following the expansion of the offence, and more survivors of this form of abuse are reporting it to the police.

Many offences are not charged, although suspects have been identified

The data is less encouraging when looking at crime outcomes. In only about 4% (n=534) of all offences recorded across the 24 police forces from January 2019 to July 2022, was the alleged offender charged or summonsed. The table below breaks this result down by individual police force. Only one police force charged/summonsed more than 10% of recorded offences – Bedfordshire. Four out of the 24 police forces recorded more than 1,000 offences each. None of them charged more than 4% of its recorded offences.

Table 2: Charging rates by police force

| Police force | Number of offences charged/summonsed | Number of overall revenge porn offences recorded (Jan 2019 – July 2022) | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedfordshire | 30 | 262 | 11% |

| Cambridgeshire | 21 | 306 | 7% |

| Cheshire | 15 | 269 | 6% |

| City of London | 0 | 2 | 0% |

| Cumbria | 10 | 196 | 5% |

| Devon and Cornwall | 19 | 583 | 3% |

| Dorset | 17 | 306 | 6% |

| Durham | 12 | 351 | 3% |

| Greater Manchester Police | 55 | 1347 | 4% |

| Gwent | 9 | 227 | 4% |

| Hertfordshire | 7 | 269 | 3% |

| Lancashire | 18 | 993 | 2% |

| Leicestershire | 22 | 485 | 5% |

| Merseyside | 49 | 755 | 6% |

| Met | 87 | 3356 | 3% |

| North Wales | 18 | 311 | 6% |

| North Yorkshire | 18 | 196 | 9% |

| Northamptonshire | 11 | 296 | 4% |

| South Yorkshire | 33 | 719 | 5% |

| Surrey | 7 | 203 | 3% |

| Sussex | 16 | 248 | 6% |

| Warwickshire | 14 | 186 | 8% |

| West Midlands | 28 | 1800 | 2% |

| Wiltshire | 18 | 194 | 9% |

| Grand Total | 534 | 13,860 | 4% |

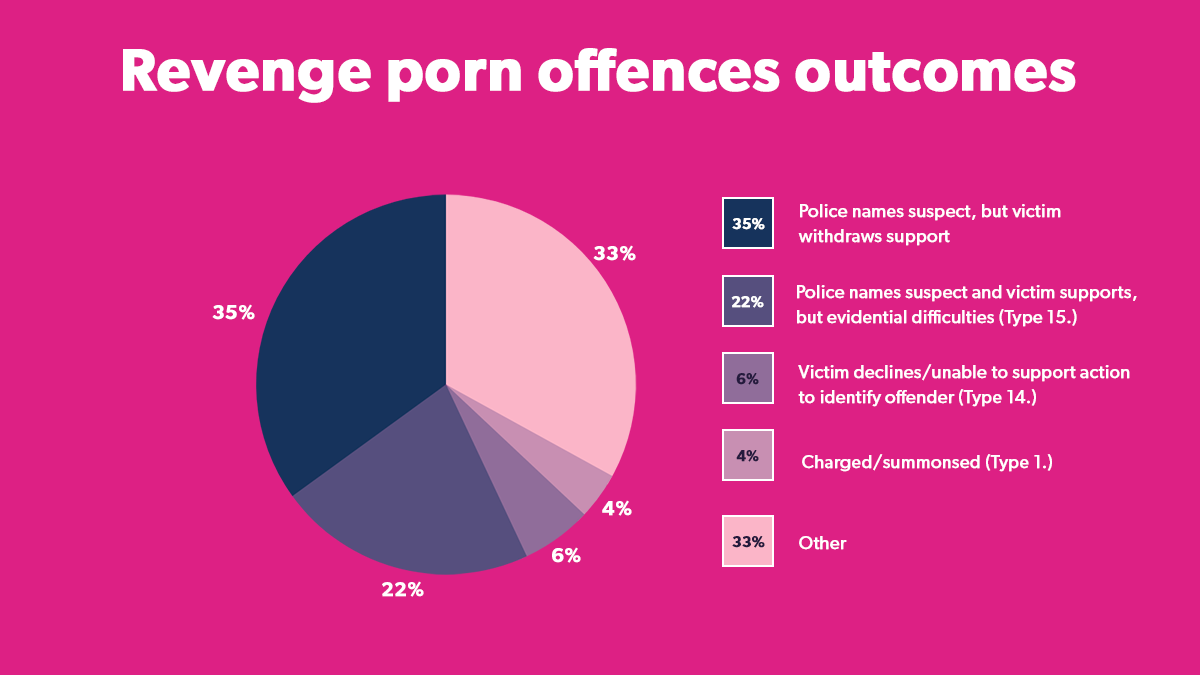

In about 35% of offences, the police identified a suspect, but no further action was taken as survivors were either unable or unwilling to support prosecution (outcome type 16). This is concerning and tallies up with the high number of domestic abuse survivors withdrawing from the criminal justice process. As mentioned in the introduction, survivors frequently have negative experiences when reporting intimate image abuse to the police. This might be because police lack essential knowledge around victims’ rights and routinely underestimate the seriousness of intimate image offences, which prevents officers from appropriately responding to reports of intimate image abuse. A significant barrier identified includes the fact that the sharing or threatening to share of intimate images is not considered a sexual offence and therefore survivors are not guaranteed anonymity.

Another 22% of recorded offences resulted in no further action due to ‘evidential difficulties’. This appears to support anecdotal evidence from our specialist tech team, who shared that, both before and since expanding the offence of sharing intimate images to include threats to share, police officers don’t appear to be aware of what evidence they would require to proceed with a case. For instance, Refuge has supported women whose own phone has been taken as evidence, rather than the perpetrator’s. Other research has also found that the requirement to prove that the image was shared with the intention to cause distress can be difficult and therefore hinder prosecution.

Equally, in some cases, police officers have told survivors that their perpetrator is likely to be asked for a voluntary initial interview, leaving survivors fearful of repercussions from their perpetrator if they are not arrested, and providing their perpetrator with a window of opportunity to delete evidence. Refuge staff have identified police failure to effectively gather evidence, and poor handling of cases, as a key factor in women’s decisions to decide not to pursue their case against their perpetrator. For many women, this contributes to feeling as though they have no other option but to return to their perpetrator, thus increasing their risk of further harm and abuse.

Table 3: Number of recorded revenge porn offences by outcome type by year by police force between January 2019 – July 2022, based on the 24 police forces that provided complete data

| Outcome | Number | Percentage of total number of offences recorded (n=13,860) |

|---|---|---|

| Cases with outcome charged/summonsed (Type 1.) | 534 | 4% |

| Cases where victim declines/unable to support action to identify offender (Type 14.) | 891 | 6% |

| Cases where police names suspect, victim supports but evidential difficulties (Type 15). | 3,029 | 22% |

| Cases where victim declines/withdraws support - named suspect identified (Type 16). | 4,886 | 35% |

| Other types of outcomes | 4,520 | 33% |

| Total | 13,860 | 100% |

Refuge’s recommendations

The current outcomes for intimate image offences across a sizable number of police forces in England and Wales indicates that further action is needed from the police to ensure that survivors can access justice and protection.

Amending the law to recognise ‘threats to share’ as intimate image abuse, and to make it a criminal offence was an important step towards protecting women from this form of domestic abuse. It is essential that government continues to update the law to reflect the way technology is misused by abusers to perpetrate violence against women and girls. However, changes to the law will only make a material difference for survivors if they are properly implemented and monitored.

Our recommendations:

- To ensure the police can effectively respond to intimate image abuse, Refuge calls for consistent training for officers across police forces, to ensure they are up to date with the law and are confident in identifying and investigating intimate image offences This training should emphasise that intimate image abuse is routinely perpetrated in a domestic abuse context, and officers must be trained to respond to survivors appropriately. Decisive action must be taken to root out the culture of victim-blaming, misogynistic language and cultural insensitivity amongst officers and improve survivors’ confidence in coming forward.

- Sharing and threatening to share intimate images are offences that are primarily committed online and therefore there will often be digital evidence, yet many cases are not proceeding due to difficulties in the police obtaining evidence. It is vital that police forces are adequately resourced to investigate crime committed online and obtain relevant digital evidence efficiently and in a timely manner.

- Eighteen months after the intimate image offence was expanded to include threats to share, and despite sharing information from our services and survivors, Refuge has still not received any information from the Home Office and Ministry of Justice as to how they plan to monitor and improve the implementation of this change to the law. A proper monitoring plan must be put in place as a matter of urgency, based on insight from survivors and specialist VAWG services.

Refuge is the largest specialist provider of domestic abuse services in the UK, supporting more than 6,500 women and their children fleeing domestic abuse on any given day. As part of its services, Refuge has an expert tech abuse and empowerment team with staff specifically trained to support women experiencing complex technology-facilitated abuse.